In the old catalogue of Durham Cathedral Library, Codicum manuscriptorum Ecclesiae Cathedralis Dunelmensis catalogus classicus from 1825, you will find the following Fulgentius entries:

The Homilia of page 56 is in DCL, A.III.29, folio 313, part of the Homiliary of Paul the Deacon (not the manuscript I blogged on before, that was B.II.2). The Homiliae of page 98 are the afore-blogged Homiliary in B.II.2 — two homilies this time, starting on folios 4v and 29r. The third set of homilies is in another Homiliary, B.II.31, three homilies starting on folios 26, 30, and 47 according to the catalogue. These are homilies of St Fulgentius of Ruspe, who lived c. 467 – c. 532.

The Homilia of page 56 is in DCL, A.III.29, folio 313, part of the Homiliary of Paul the Deacon (not the manuscript I blogged on before, that was B.II.2). The Homiliae of page 98 are the afore-blogged Homiliary in B.II.2 — two homilies this time, starting on folios 4v and 29r. The third set of homilies is in another Homiliary, B.II.31, three homilies starting on folios 26, 30, and 47 according to the catalogue. These are homilies of St Fulgentius of Ruspe, who lived c. 467 – c. 532.

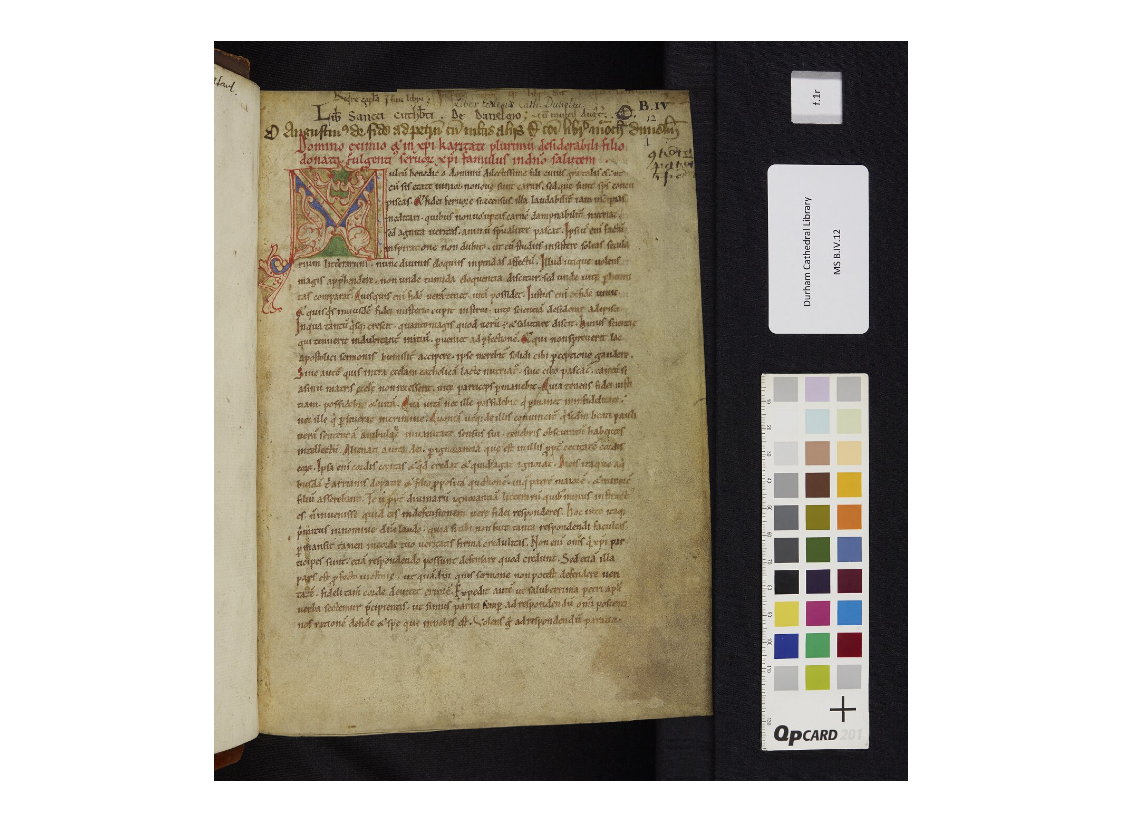

The next item is the Epistola de Fide. This text is in B.IV.12, starting folio 1r:

This is an anti-Arian tract by Fulgentius of Ruspe, Ep. 8 of his correspondance.

Then we have Comm. in Mythologiae, found in B.IV.38, starting folio 92, the Commentarius in Fulgentii Mythologias. This is a commentary on the Mythologiae of Fabius Planciades Fulgentius, a fellow African who live around the same time as the Bishop of Ruspe but is a different person altogether. Some have previously thought them the same, but, as I understand it, scholarly consensus today divides our two Fulgentii.

What is strange about this index is that, after the commentary on the other Fulgentius, we are directed to the De Fide ad Petrum in DCL B.II.27 by Fulgentius Ruspensis, as though this were a work by a different person. I assume the index was compiled by someone different from the catalogue itself, since it gives the impression that we have two Fulgentii, but divides the works wrong.

Why does this matter? Well, I have an interest in Fulgentius of Ruspe as someone who was influenced by the theology of Leo the Great and engaged in what some call ‘the Arian controversy 2.0’ — he shows the sixth-century synthesis of earlier theology. I am, perhaps, less interested Fulgentius the mythographer, but he is still worthy of interest for me as an intellectual historian whose work, when not analysing mediaeval canon law, looks at the fifth century.

For both Fulgentii, mansucripts are important. In fact, manuscripts are important for all pre-print authors. Studying them helps us understand the authors better. Textual criticism brings us closer to their own words as well as showing us how they were read and interpreted in history. Furthermore, in a library like Durham’s, it is worth knowing which authors were transcribed and read. One of my hypotheses I want to test is the idea of canon law as theology, and the only way to do that is to consider the non-canon law books from the same library.

If we can’t keep our Fulgentii straight, we’ll have trouble understanding the history of ideas and manuscripts.

Anyway, all of this to say: I do look forward to Richard Gameson’s catalogue when it is finished. And I look forward to the day when all of these opera Fulgentii are digitised and can be worked on from the comfort of my own office.