I have come to the study of medieval canon law from the study of late antique papal letters and their transmission — a transmission that is almost entirely through medieval manuscripts, and usually (but not always) manuscripts used as material for canon law. Canon law, whether seen as a scientia of its own or as a realm of knowledge subsumed within theology, mines the late antique church for its material sources. For the purposes of this post, I will take a long-ish view of ‘late antique’, say, Marcus Aurelius to Mohammed (following, then, Peter Brown’s The World of Late Antiquity) — as far as these manuscripts are concerned, that would be Tertullian to Isidore of Seville. At a certain level, medieval Christianity could be seen (up to certain stages of late scholasticism) as one long reflection and reception of late antique Christian thought.

Already on this blog I have highlighted this late antique, or ‘patristic’, presence in Durham’s manuscripts. In my Christmas post, I discussed Paul the Deacon’s Homiliary of patristic sermons. In my discussion of canon law, I talked about DCL B.IV.18, a collection of largely late antique excerpts not only of canon law but also of theology. Nowhere do we better see the patristic heart of Benedictine intellectual life than in the donation list of William of St Calais.

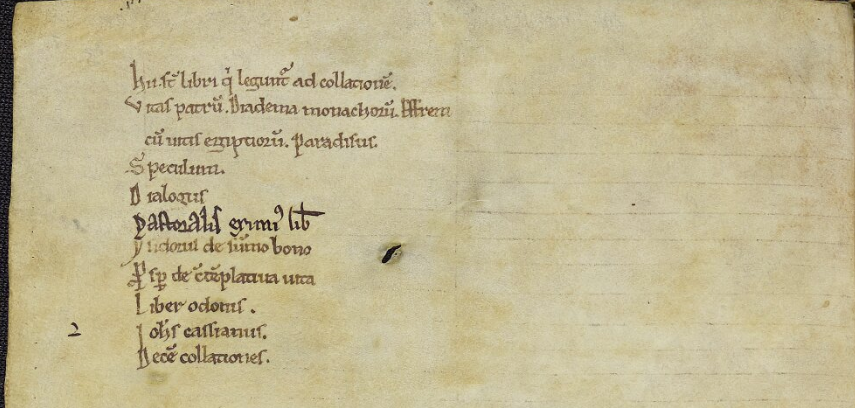

Another book list written by the hand of Symeon of Durham is likewise central to Benedictine life and likewise patristic — this is the list of books to be read at Collatio in DCL B.IV.24:

- Vitae Patrum

- Diadema Monachorum

- Effrem cum Vitis Egiptiorum Paradisus

- Speculum

- Dialogus

- Pastoralis, eximius Liber

- Ysidorus de Summo Bono

- Prosper de Contemplativa Vita

- Liber Odonis

- Johannes Cassianus

- Decem Collationes

Most, but not all, of these texts are late antique — lives of the Desert Fathers, Ephrem the Syrian, Gregory the Great’s Dialogues, Gregory’s Book of Pastoral Rule, Isidore of Seville’s De Summo Bono, Prosper of Aquitaine’s On the Contemplative Life, John Cassian’s Conferences (or Collationes in Latin — whence, in fact, comes the name of collatio in Benedict’s Rule).

Of course, the absolutely most important late antique book in any Benedictine monastery is the Rule of St Benedict itself — its importance at Durham is highlighted by its presence not only in the original Latin but in an Old English translation as well. It is found, along with the list of books to be read at Collatio, in the Durham Cantor’s Book.

Many other late antique texts could be discussed (Chrysostom, Augustine, Isidore) but I’ll mention only one more, and that is a book that pre-dates the refounding of the community by William of St Calais in 1080 — the Durham Cassiodorus, DCL B.II.30. This manuscript is a copy of Cassiodorus’ commentary on the Psalms. It is one of a few pre-Conquest Durham manuscripts that were believed by some of the monks to have been written by the Venerable Bede. While Bede was probably not one of the six scribes to work on this text, it is nevertheless a manuscript that probably came from the twin monasteries of Wearmouth-Jarrow in the second quarter of the 700s — so within Bede’s lifetime at Bede’s monastery.

Cassiodorus’ Psalm commentary was very popular in the Middle Ages, which only makes sense. Benedictines sing the whole book of Psalms every week. A commentary like Cassiodorus’ would help them focus their minds on the true interpretation of the words their lips recited. In this manuscript, then, we have the convergence of Benedictine psalm-singing, late antique commentary, and Northumbrian manuscript culture. It is, in a way, a codex microcosm of Durham Priory’s ideal self.

These are but a few of the late antique texts stored in Durham Cathedral Priroy’s manuscripts. I have only scratched the surface. What is probably a more interesting story is how these manuscripts were used by the monks in their own lives and thought. That question is more difficult, of course, and both are inevitably frayed at the edges — for, even if we have so many Durham manuscripts, there are still others we lack.