De proprietatibus rerum (Durham Cathedral Library Inc.3)

The digitisation of medieval books and manuscripts is generally a pretty straight forward process; provided you have the right equipment and you take the time to do it carefully. The Priory Library Recreated Project uses conservation copy stands, also known as ‘book cradles’ (there is a photo of one in action on the homepage). We have a well-established workflow, and most books and manuscripts take around two weeks to digitise.

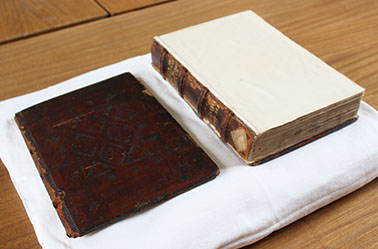

Now and again however, we have to tackle something that presents a bit more of a challenge and requires a little creativity. Recently, we were asked to digitise one of Durham Cathedral Library’s incunables (early printed books) which, having been in use since it was printed in 1491, is unfortunately now damaged, with both of its 15th/16th century front and back boards having become completely detached. De proprietatibus rerum (‘On the Properties of Things’) by Bartholomeus Anglicus is an encyclopedia first written in the early 13th century. It contains 19 books covering a variety of topics such as religion, medicine, geography, astronomy and the natural sciences. Our copy has been heavily annotated by Thomas Swalwell, a monk of Durham who lived from approximately 1483 until 1539. Besides his notes on almost every page, he has also added a glossary index and an index of herbs to our volume. This makes the book a particularly interesting copy of an already significant text.

When digitising books of this age, a solid binding is important because it protects and supports the delicate paper or parchment during the process. Although De proprietatibus rerum is rather badly damaged, because it is still quite frequently used, we felt it was important to digitise it, as having a digital copy will of course reduce the need to handle it.

Our book cradles allow a book to lay open to about 110 degrees, and the camera is positioned to capture one page at a time, so we digitise all of the rectos, then turn the book around and digitise all of the versos.

The first challenge was simply putting the book on the cradle. We considered whether to try to place the volume with its boards in position (which may have caused the three separate parts to slip around), or to leave the boards off (which would have left the outer leaves of the text block with no protection). In the end, we decided on a bit of both. Leaving the board underneath the text block gave it some stability and protection, but the other board could not be placed in any useful way, so had to be set aside. However, as predicted, this left the unprotected pages sort of floating around, with nothing to rest against. We decided to make a false board in the shape of a wedge, to bridge the gap between the pages and the cradle, and to enable pages which had been digitised to be strapped down securely. We used some old exhibition mounts (we like to recycle here!) to make a hinged wedge, which could be adjusted as the book opened further and changed position.

In all honesty, this did not go perfectly first time round. The way that we had initially planned to use the hinged wedge didn’t work at all, and we had to try it round every which way until it fell into the perfect position, which ultimately happened though luck as much as judgement. Still – it doesn’t matter how you get there, as long as you get there in the end!

We also added an extra layer of thin foam underneath the book to cushion it a bit more, and used foam blocks to support the spine and pages when necessary. As we got further through the book (after about forty pages), we were able to turn the wedge around so that its thin end was towards the spine, matching the angle of the spine as the book opened more. We continued to adjust the wedge until eventually, it was no longer needed at all. We then did the whole thing more or less in reverse when we digitised the versos.

We would normally use the book cradle to photograph the covers, spine and edges of books and manuscripts as well, but in this case the book was too badly damaged to be properly supported during this process. Fortunately we also have a Guardian International copy stand here (for digitising flat documents) and so, after experimenting with the best way to support the volume, we used that instead. This set-up also enabled us to use raked lighting (lit from one side only) on the binding, which is beautifully decorated with tooled leather. By lighting the book from one side and adjusting the high dynamic range (highlight and shadow) of the image, we were able to make a lot more of the delicate tooled decoration visible. Of course, these images are not colour accurate, but they show a level of detail that is hard to see on a normal photograph, or even with the naked eye.

There was no great complexity to what we did, but the simplest solutions are often the best (and cheapest). Our two bits of board, some foam and a bit of tape enabled us to successfully digitise a fragile book, which can now be enjoyed anywhere in the world, while it remains safe and sound in the Cathedral Library.